Synchrony in Infant Development and Beyond: Improving Childhood Attachment With Parent-Child Bonding

The parent-child relationship has been a focus of psychology for many decades. Ever since the introduction of attachment theory in the 1960s, research on infant-caregiver bonds and their impact on child development has grown tremendously.1

Findings consistently show that the first attachment bond a child forms becomes the foundation of their emotional, psychological, and relational health. It also plays a powerful role throughout childhood, adolescence, and even adulthood.2,3

For this reason, it’s important that steps are taken to improve early attachment in a timely way. Fortunately, research in developmental psychology has shown that the concept of parent-child synchrony – the emotional and physiological alignment between caregiver and child – can offer insight into how to strengthen bonds.4

If you’d like advice on how to strengthen the emotional connection between you and your child, a mental health professional can offer help and support. This article can also work as a guide, exploring:

- What parent-child synchrony in psychology is

- How synchrony influences emotional and psychological development

- Signs of disrupted synchrony and attachment trauma

- Evidence-based approaches to improving parent-child bonding

- Types of therapy for attachment repair

- How synchrony-focused interventions support mental health outcomes in families

What Is Parent-Child Synchrony in Psychology?

Parent-child synchrony refers to the verbal and nonverbal coordination in the interaction between a child and their caregiver. When there’s synchrony, both parties are attuned to each other and match on behavioral, emotional, and even physiological levels.

This type of connection and reciprocity within their communication is sometimes compared to a dance. This is because synchrony is not about a single behavior, but rather about the overall impression that both parties are on the same page.5,6

When there’s synchrony, there’s a match between facial expressions, vocalizations, gaze, touch, and posture that align in time, reflecting a shared emotional and physiological state.4 Signs of high synchrony include high levels of warmth, responsiveness, and positive mood, as well as joint attention.7

Parent-Child Synchrony and Emotional Development

Parent-child synchrony is not just about a good relationship between a parent and child. Rather, it’s about a profound level of attunement that shows up in how each party pays attention to and reacts to the cues of the other.

This type of reciprocity makes communication feel predictable and safe – especially for the child. Therefore, it’s not surprising that research consistently links positive parent-child synchrony with good mental health outcomes. For instance, studies have repeatedly shown that synchrony is strongly linked to the child’s regulation, attachment, and social development.4,5,7

As synchrony facilitates parent-child co-regulation, it boosts a child’s confidence when it comes to dealing with negative emotional states, and their ability to self-soothe later in life.5 Syncing to a caregiver has also been found to foster a child’s self-awareness and self-control.12 Children who grow up in such an attuned and connected social context typically develop good social and emotional skills, leading to the likelihood of healthy relationships later in life.13

Furthermore, parent-child synchrony is believed to contribute to secure attachment in infants, as attunement in interactions with caregivers creates a sense of security and connectedness.6-10 As a result, a child learns that relationships can be trusted and is likely to develop a healthy, secure attachment style.6

Disrupted Synchrony and Attachment Trauma

There are various reasons why parent-child synchrony in early development might be disrupted. For instance, caregivers who struggle mentally could find it difficult to stay in tune with their children, which is understandable, given that their psychological state is not calm and balanced. Additionally, life stressors, such as adversity, can also contribute to parental inconsistency or misattunement.14

When synchrony is disrupted, the child’s development might be affected negatively on emotional, relational, and behavioral levels. For instance, a lack of parent-child synchrony has been linked to insecure attachment, poor emotion regulation, reduced communication and self-control, and greater risk for anxiety, aggression, and neural dysregulation.4,5,7,13,14

Research also links disrupted synchrony and attachment trauma, showing how attachment issues in parents can affect the attachment styles of children from a very early age. Typical signs of attachment trauma that have been observed in infants include:15,16

- Social withdrawal

- Increased levels of stress

- Higher levels of separation anxiety

- Inability to use the caregiver as a stress buffer

- Lower ability to soothe

- Disrupted behavior towards the caregiver

The negative effects of attachment trauma start to manifest early in life, but it’s also essential to note that they often progress further down the child’s lifespan. For example, evidence shows that attachment disturbances can show up as mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression in adolescence and adulthood.15

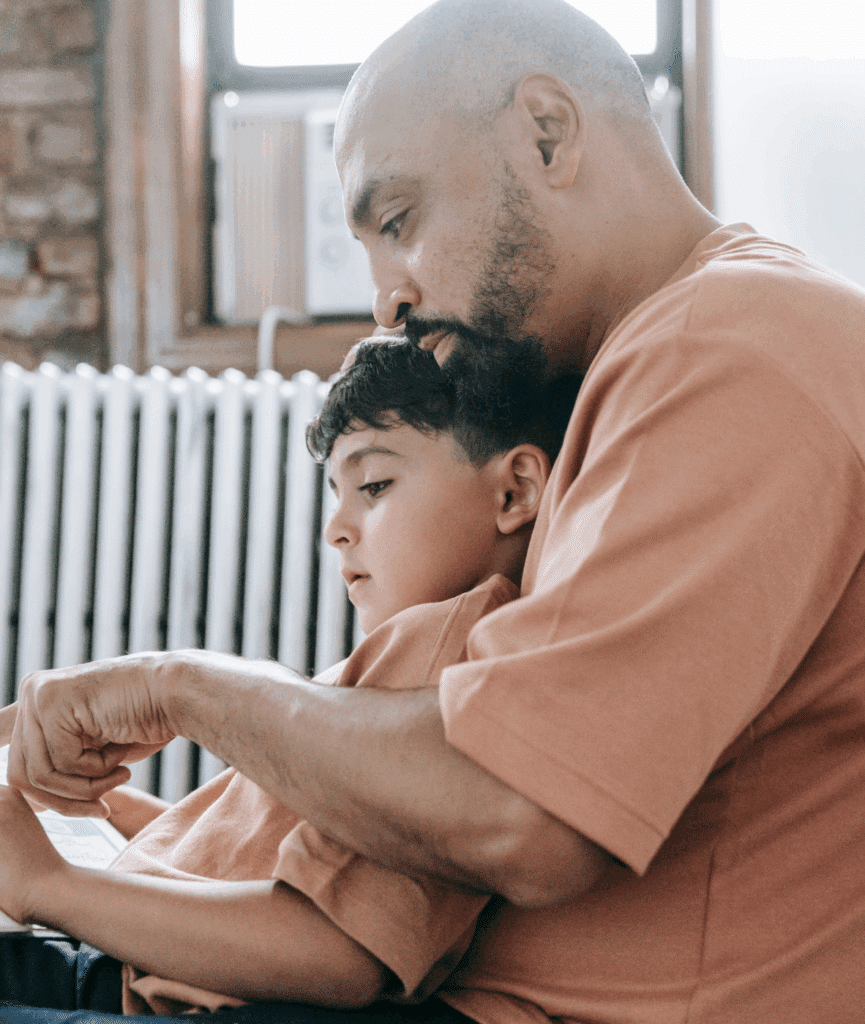

Improving Parent-Child Attachment Bonding

Improving parent-child attachment bonding might require intentional effort, but it is possible and in the child’s best interest. Given the importance of early attachment and parent-child synchrony, caregivers are recommended to explore secure attachment parenting strategies and pay attention to how they connect to their babies early on.

According to early work on attachment developed by Mary Ainsworth, parental responsiveness is a complex construct that can be viewed across multiple dimensions, such as:14,15

- Sensitivity-insensitivity

- Cooperation-interference

- Availability-ignoring

- Acceptance-rejection

All of these factors can contribute to the depth and security of the connection and enhance synchrony for secure attachment. When it comes to improving parent-child attachment bonding, caregiver sensitivity, nurturance, and synchrony seem to be of particular importance.

Fortunately, there are ways to foster such positive interactions within the parent-child relationship. Based on studies that investigated secure attachment parenting strategies, parents are recommended to:18

- Respond to cues of distress from their children by soothing and rebuilding safety

- Remain present in non-distressing situations, such as responding to positive events with enthusiasm, interest, and validation

- Pay attention to and interpret the child’s body language, vocal cues, and facial expressions

- Try to stay attuned to the child’s emotional state and offer appropriate responses

- Prioritize consistency, predictability, and safety within communication

- Avoid demonstrating high-anxiety and high-stress responses

One key factor in cultivating synchrony is the caregiver’s own emotional regulation and mental balance. Children learn to regulate by co-regulating with an attuned, well-balanced adult. If a parent struggles with anxiety, trauma, or nervous system dysregulation (such as being in fight-or-flight mode), they are advised to address these issues before reacting to their child.18

Therapy for Parent-Child Attachment Repair

Parent-child synchrony and attachment issues can strongly benefit from the support of mental health professionals. Therapy can assist caregivers in tuning into their child’s state and creating a safe and nurturing connection.

Through attachment-based parenting therapy, which focuses on helping caregivers understand how their own attachment history influences their parenting, caregivers can improve self-awareness and responsiveness to the cues of their child .

Common therapeutic approaches include:17,18,19

- Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT): Uses structured play sessions and live coaching to increase warmth, reduce negative behaviors, and improve attunement.

- Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy (DDP): Integrates attachment theory and trauma-informed care to build emotional trust and co-regulation.

- Circle of Security Parenting (COSP): Guides caregivers in recognizing their child’s emotional needs and responding in positive ways that contribute to attachment security.

These approaches can differ in intensity and delivery based on the needs of the family and the severity of relational issues between caregivers and their child.

Supporting Parent–Child Synchrony and Attachment Through Intervention

When it comes to mental health treatment for attachment issues in families, parental sensitivity and nurturance are seen as two key factors in parent-child synchrony.18 Sensitivity on the side of the parent involves accurately reading a child’s cues and responding to these with appropriate, timely, and positive, supportive actions. This is especially important when the child is actively seeking attention or a response from them.

Evidence shows that programs such as Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, and Playing and Learning Strategies (PALS) demonstrate how caregiver behaviors can shift relatively quickly through structured support. These interventions work by both reducing harshness and increasing attunement.18

Some interventions focus on real-time feedback given to the parent during a session.18 Others entail more flexible approaches that include education through media and self-directed programs.20 Such initiatives are typically effective and promote better parent-child synchrony and attachment.

Inpatient Programs for Parent Child Attachment Work

Mission Connection: Improving Parent-Child Attachment Bonding

No parent is perfect, and no “ideal” parenting style or approach fits all situations and contexts. However, guidelines and resources provided by mental health professionals can significantly improve parent-child synchrony and attachment. Psychological support and parent-child synchrony interventions are especially important in cases of attachment trauma and disrupted synchrony.

If you’re struggling in your relationship with your child or are worried about someone you love, Mission Connection can guide you through the options for mental health treatment for attachment issues in families.

Our team is committed to supporting families through the challenges of attachment disruption and trauma. We would be more than happy to offer insight and support on secure attachment parenting strategies and enhancing synchrony for secure attachment. Our trauma-informed clinicians provide individualized care that centers synchrony, emotional safety, and long-term attachment healing.

If you’re ready to explore therapeutic options for your family or for someone you love, reach out. Help is available, and developing secure attachment and strong synchrony with your child is possible.

References

- Bowlby, J. (1958). The nature of the child’s tie to his mother. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 39, 350–373.

- Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2009). An overview of adult attachment theory. Attachment theory and research in clinical work with adults, 17-45.

- Cohen, D. (2012). The developmental being: Modeling a probabilistic approach to child development and psychopathology. In M. E. Garralda & J. Raynaud (Eds.), Brain, mind, and developmental psychopathology in childhood (pp. 3–29). Jason Aronson.

- Feldman, R. (2007). Parent–infant synchrony: Biological foundations and developmental outcomes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00532.x

- Quiñones-Camacho, L. E., Hoyniak, C. P., Wakschlag, L. S., & Perlman, S. B. (2022). Getting in synch: Unpacking the role of parent-child synchrony in the development of internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Development and Psychopathology, 34(5), 1901–1913. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579421000468

- Delaherche, E., Chetouani, M., Mahdhaoui, A., Saint-Georges, C., Viaux, S., & Cohen, D. (2014). Interpersonal synchrony: A survey of evaluation methods across disciplines. PLOS ONE, 9(12), e113571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113571

- Alonso, A., McDorman, S. A., & Romeo, R. R. (2023). How parent–child brain-to-brain synchrony can inform the study of child development. Child Development Perspectives, 18(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12494

- Isabella, R. A., & Belsky, J. (1991). Interactional synchrony and the origins of infant-mother attachment: A replication study. Child Development, 62(2), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131002

- Isabella, R. A., Belsky, J., & Von Eye, A. (1989). Origins of infant–mother attachment: An examination of interactional synchrony during the infant’s first year. Developmental Psychology, 25(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.25.1.12

- Leclère, C., Viaux, S., Avril, M., Achard, C., Chetouani, M., Missonnier, S., & Cohen, D. (2014). Why synchrony matters during mother–child interactions: A systematic review. PLOS ONE, 9(12), e113571. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113571

- Barber, J. G., Bolitho, F., & Bertrand, L. (2001). Parent-child synchrony and adolescent adjustment. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 18(1), 51-64.

- Feldman, R., Greenbaum, C. W., & Yirmiya, N. (1999). Mother–infant affect synchrony as an antecedent of the emergence of self-control. Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 223–231.

- Lindsey, E. W., Creemeens, P. R., Colwell, M. J., & Caldera, Y. M. (2009). The structure of parent–child dyadic synchrony in toddlerhood and children’s communication competence and self-control. Social Development, 18(2), 375–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00489.x

- Hoyniak, C. P., Quiñones-Camacho, L. E., Camacho, M. C., Chin, J. H., Williams, E. M., Wakschlag, L. S., & Perlman, S. B. (2021). Adversity is linked with decreased parent–child behavioral and neural synchrony. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 52, 100937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2021.100937

- Naeem, N., Zanca, R. M., Weinstein, S., Urquieta, A., Sosa, A., Yu, B., & Sullivan, R. M. (2022). The neurobiology of infant attachment-trauma and disruption of parent–infant interactions. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 16, Article 882464. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2022.882464

- Bernard, K., Meade, E. B., & Dozier, M. (2016). Parental synchrony and nurturance as targets in an attachment based intervention: building upon Mary Ainsworth‘s insights about mother–infant interaction. In Maternal Sensitivity (pp. 65-81). Routledge.

- Ainsworth, MDS.; Blehar, MC.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, N.J.: 1978.

- DePasquale, C. E., & Gunnar, M. (2020). Parental sensitivity and nurturance. The Future of Children, 30(2), 53–70.

- Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy Network. (n.d.). About DDP: Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy. https://ddpnetwork.org/about-ddp/dyadic-developmental-psychotherapy/

- Sanders, M. R. (1999). Triple P–Positive Parenting Program: Towards an empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavior and emotional problems in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2(2), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021843613840