Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans: Treatment Options

For many veterans, the battle doesn’t end when the deployment does. Long after coming home, the mind can stay on high alert, flooded by memories that don’t fade and haunted by sights, sounds, or smells that bring everything rushing back.

If this sounds familiar to you, you’re not alone, and you are certainly not beyond help.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a natural response to the unnatural things you’ve seen and survived. Decades of research and thousands of veteran success stories show that with the right care, PTSD can be treated with evidence-based, veteran-informed therapies.

A mental health professional can help you or someone you care about overcome the effects of PTSD in veterans. This page can also help, covering the “gold-standard” PTSD treatments for veterans recommended by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Department of Defense (DoD), including:

- VA and DoD guidelines for the management of PTSD in veterans

- Evidence-based therapies for PTSD in military veterans

- Medication options for PTSD in veterans

- New and complementary therapies for PTSD

- Group therapy and peer support for PTSD

- How to prevent PTSD relapse in veterans

- Where to find professional support for PTSD in veterans

VA and DoD Guidelines for Management of PTSD in Veterans

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Department of Defense (DoD) came together to update their PTSD treatment guidelines for veterans in 2010.1

These guidelines were created by a diverse, deeply experienced team that included mental health professionals, physicians, nurses, social workers, and medication experts. Plus, all the recommendations made are grounded in research.

This team strongly encourages starting PTSD treatment with a combination of evidence-based psychotherapy and medication. Among the most effective approaches is trauma-focused therapy for veterans that includes:

Prolonged exposure (PE)

Cognitive processing therapy (CPT)

Stress inoculation training (SIT)

The guidelines also advise against the use of psychological debriefing immediately after trauma. This is a method where veterans are made to talk about their trauma right after they’ve endured it, but it sometimes does more harm than good.

For medications, the guidelines suggest that antidepressants, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), may be taken for symptom relief. But benzodiazepines are not recommended, as the risks they pose outweigh their benefit in treating PTSD.

In the sections ahead, you’ll learn about each of these treatment options in more depth.

Evidence-Based Therapies for PTSD in Military Veterans

The four most commonly used trauma-focused therapies in PTSD treatment for veterans include:

1. Prolonged Exposure Therapy

During PE, you’ll learn about PTSD and the science behind how trauma affects the brain. Then your therapist will help you create a list of trauma-related things you’ve been avoiding. Examples include things like driving on highways, going to crowded places, or looking at a military uniform.

These are what we call “in vivo exposures.” You’ll practice approaching these situations at your own pace. Yet, as you build confidence, you’ll likely begin imaginal exposure, which is talking through the traumatic memory itself in a safe, guided way.3

During prolonged exposure, these sessions will be recorded, giving you the chance to listen back between visits. This repetition can help rewire the brain’s fear response. Thus, over time, people often find that their intrusive memories fade and their self-trust grows stronger.

Prolonged exposure is not always easy, but it’s the natural work of healing. And you’re never alone in it.

2. Cognitive Processing Therapy for Veterans

Cognitive processing therapy has been shown time and again to be one of the most effective treatments for PTSD. It is one of the two frontline trauma therapies most widely used across the VA system.4

CPT lasts for 12 weekly sessions. In your first few sessions, your provider will walk you through how trauma affects your brain and body, and help you recognize how your trauma has shaped certain beliefs. However, you’ll never be pushed into sharing anything you’re not ready for.

You may also be asked to write about how your trauma has impacted your life. Then, session by session, you and your therapist will look at the negative thoughts you’ve been holding onto using simple, structured worksheets to gently challenge them.5

By the end of CPT treatment, you’ll likely have worked through the areas of life that trauma disrupts, like safety, trust, power, self-worth, and intimacy. A culture shock to many people – any Vet will agree that it takes getting used to.

While training, you’re separated from your family. And some Vets say you swap out your individuality for becoming part of a strong military unit. What’s more, your time is managed by someone else – you are essentially trusting another person to control your time and daily living habits for months on end.

And finally, training and the military culture are tough to endure and can be extremely physically and psychologically stressful.3

3. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing

Instead, EMDR therapy for PTSD helps your brain “unstick” traumatic memories through a series of structured mental exercises. It is paired with bilateral stimulation through eye movements, tapping, or sound.

During EMDR sessions, you hold the painful memory and emotions in your mind while following a back-and-forth visual cue. This cue might be your therapist’s finger moving side to side, or a light or sound alternating left to right. The stimulation helps your brain reprocess and reorganize the traumatic material so it no longer feels dangerous.

EMDR has been studied in multiple clinical experiments and is recognized by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense as an evidence-based PTSD treatment for veterans.6

4. Stress Inoculation Therapy

In the same way a vaccine prepares your immune system to fight off illness, SIT helps you practice specific, personalized coping strategies to fight off the stress that PTSD brings. It includes:

Deep, diaphragmatic breathing- Progressive muscle relaxation

- Thought awareness and restructuring

- Role-playing real-life anxiety-provoking scenarios to practice your response

- Recordings or scripts to practice coping strategies at home

SIT acknowledges that for some people, the idea of revisiting traumatic experiences isn’t a good fit. While it may not be as effective as other trauma-focused therapies, it still shows real benefit in clinical experiments.7

Medication for PTSD in Veterans

The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense both recommend three medications as first-line treatments for PTSD on equal footing with psychotherapy. These are:

Sertraline (Zoloft)- Paroxetine (Paxil)

- Venlafaxine (Effexor XR)

All these medications belong to the SSRI/SNRI class of drugs and have been extensively studied. Plus, a Cochrane analysis, considered one of the gold standards in medical research, found that SSRIs and SNRIs are effective in both short-term and long-term treatment of PTSD.8

Another study compared medication and psychotherapy for combat-related PTSD and found that medication led to greater symptom reduction within the first six months.9 This isn’t to say medications are better than therapy, but that they can bring relief to some veterans who are unable to engage in therapy right away.

Emerging and Complementary Therapies for PTSD

Research on PTSD treatment for veterans has also brought forward several new therapies. They aren’t independently sufficient as of yet, but when combined with trauma-focused behavioral therapy, they can bring good results. Here are some examples:

Neurofeedback

It has been shown to have some benefits in PTSD treatment, as, in one study, veterans with PTSD underwent neurofeedback and showed lasting improvement 30 months later.10

Animal-Assisted Therapy

Veterans who train service animals for others often describe a profound sense of purpose. For instance, programs at places like Walter Reed Army Medical Center’s Warrior Transition Battalion have shown that even severely affected veterans can find emotional grounding through animal bonds.3

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is the ancient practice of placing tiny needles at specific points on the body. This non-verbal, body-centered approach may even rival certain therapies in reducing PTSD symptoms in veterans. Plus, it could especially improve outcomes when combined with CBT.

Electro-Convulsive Therapy

ECT does not fully resolve PTSD on its own, but it can make veterans more responsive to other forms of therapy afterward.

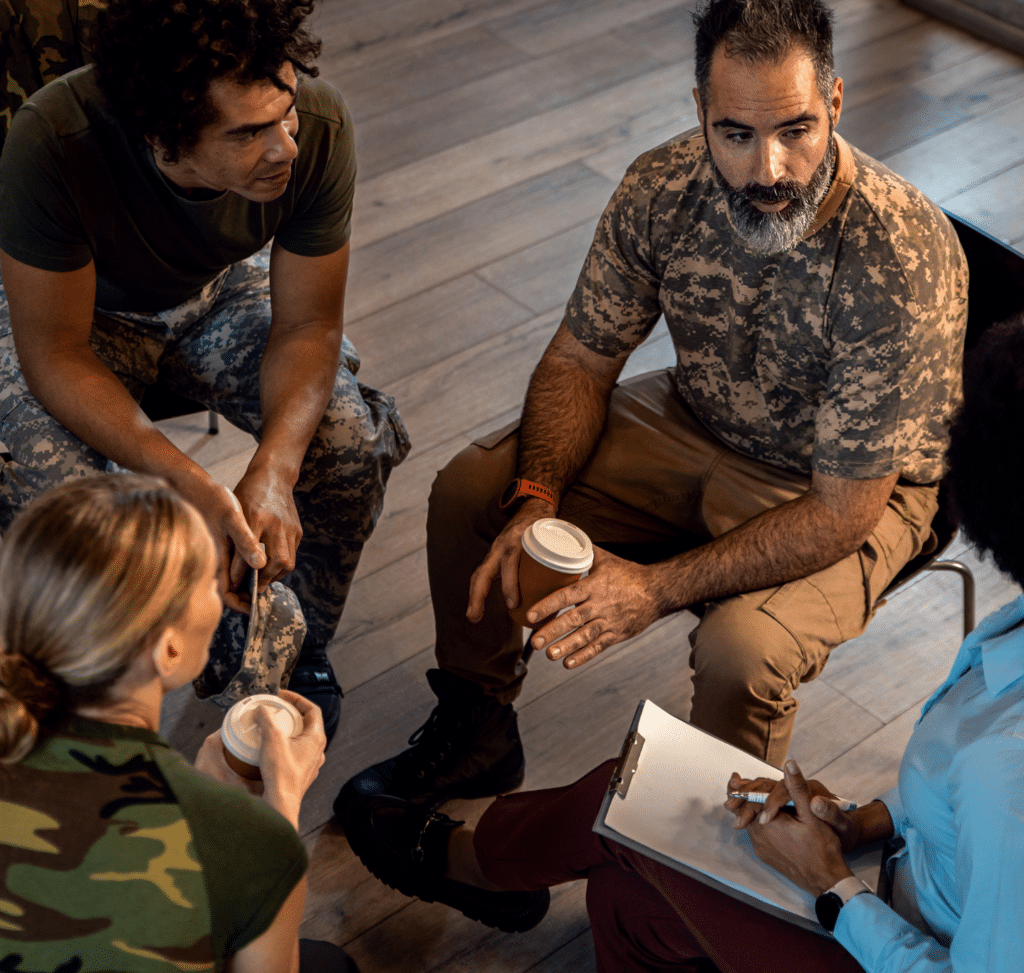

Group Therapy and Peer Support for PTSD

It’s not that people don’t care; rather, they don’t really understand. They haven’t been there. They don’t speak the same language of combat, loss, adrenaline, and what it feels like to come home with your body intact but your mind still stuck in the battlefield.

This is why peer support groups exist. They are led by a fellow veteran who has also walked through trauma and is now using that experience to hold space for others.12 Therefore, they connect you with people who have suffered through the same.

Peer groups meet in person in VA hospitals, Vet Centers, community halls, or on online forums that you can access from home. During group discussions, you talk about:

How to manage nightmares and flashbacks- What to do when your anger threatens to boil over

- How to work through VA claims, therapy options, or tough family conversations

- The guilt of surviving when others didn’t

- What it feels like to lose your sense of purpose and how to rebuild it

Some groups also do meditation or guided breathing together. So, when all of these factors are combined, peer support during PTSD treatment for veterans can deeply improve emotional health and resilience.13

You can find a support group through:

VA PTSD treatment programs at your local VA hospital’s social work department- Vet Centers in your area

- Wounded Warrior Project, Team Red, White & Blue, and Give an Hour

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)

Maintenance Treatment and Risk of PTSD Relapse in Veterans

Clinical observations suggest that veterans who return for periodic therapy sessions after completing a full course of trauma-focused therapy tend to be better for longer. However, these maintenance sessions are shorter and less frequent than regular therapy.

Management of long-term PTSD in veterans helps with:

Monitoring for early signs of relapse- Reinforcing coping skills learned in earlier therapy

- Addressing new stressors that could reactivate old trauma patterns

- Processing secondary or delayed-onset trauma

If your symptoms creep back even on medication, or if you don’t respond well to SSRIs alone, research supports augmentation strategies. In other words, your doctor may add a second medication, such as an antipsychotic, particularly for combat-related trauma.

Comprehensive PTSD Treatment for Veterans at Mission Connection

At Mission Connection, we understand that military trauma is complex and deeply personal. We take the time to understand your story, pain, strengths, and goals so that we can lead you toward a PTSD-free future.

Our experienced trauma therapists specialize in working with veterans, using gold-standard, evidence-based treatments like EMDR and trauma-focused CBT to ease PTSD symptoms.

If you or someone you love is struggling with PTSD after military service, Mission Connection Healthcare is just a call away. Contact our team today to find out more about how we can help.

References

- Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense. (n.d.). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of post-traumatic stress. The Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Working Group. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/cpgPTSDFULL201011612c.pdf

- Goodson, J. T., Lefkowitz, C. M., Helstrom, A. W., & Gawrysiak, M. J. (2013). Outcomes of Prolonged Exposure Therapy for Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(4), 419–425. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21830

- Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Effects in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, & Institute of Medicine. (2012, July 13). Treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military and veteran populations: Initial assessment (Chapter 7, Treatment). National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201108/

- Kaysen, D., Schumm, J., Pedersen, E. R., Seim, R. W., Bedard-Gilligan, M., & Chard, K. (2014). Cognitive Processing Therapy for veterans with comorbid PTSD and alcohol use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 39(2), 420–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.016

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2025). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD – PTSD: National center for PTSD. Va.gov. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand_tx/cognitive_processing.asp

- Carlson, J. G., Chemtob, C. M., Rusnak, K., Hedlund, N. L., & Muraoka, M. Y. (1998). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EDMR) treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024448814268

- Jackson, S., Baity, M. R., Bobb, K., Swick, D., & Giorgio, J. (2019). Stress inoculation training outcomes among veterans with PTSD and TBI. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(8), 842–850. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000432

- Stein, D. J., Ipser, J. C., Seedat, S., Sager, C., & Amos, T. (2006). Pharmacotherapy for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd002795.pub2

- Stewart, C. L., & Wrobel, T. A. (2009). Evaluation of the Efficacy of Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy in Treatment of Combat-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review of Outcome Studies. Military Medicine, 174(5), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-04-1507

- Peniston, E., Cemcr, V., Colorado, L., & Kulkosky, P. (1991). Alpha-Theta Brainwave Neuro-Feedback for Vietnam Veterans with Combat- Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Medical Psychotherapy, 4. https://lisasholisticrehab.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/668/2020/01/ALPHA-1.pdf

- Margoob, M. A., Ali, Z., & Andrade, C. (2010). Efficacy of ECT in Chronic, Severe, Antidepressant- and CBT-Refractory PTSD: An Open, Prospective Study. Brain Stimulation, 3(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2009.04.005

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). Peer support groups – PTSD: National Center for PTSD. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/gethelp/peer_support.asp

- Mercier, J.-M., Hosseiny, F., Rodrigues, S., Friio, A., Brémault-Phillips, S., Shields, D. M., & Dupuis, G. (2023). Peer Support Activities for Veterans, Serving Members, and Their Families: Results of a Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043628