The Link Between Eating Disorders and Attachment Trauma: Mental Health Support for Eating and Attachment Issues

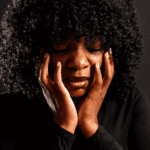

Eating disorders affect an estimated 9% of the U.S. population. That’s 28.8 million Americans.1 Of this significant number, many report histories of childhood trauma and insecure attachment. And this link is backed up by research.

Attachment trauma typically develops due to inconsistent, rejecting, or chaotic early caregiving relationships. It can disrupt a person’s sense of safety and self-worth, and may continue into adolescence and adulthood if healing experiences aren’t encountered.

Eating disorders, on the other hand, are psychiatric conditions. They involve unhealthy eating patterns that arise as a way to manage emotions.

If you’re concerned about disordered eating in yourself or someone you care about and think this may be linked to early childhood, professional support is advised. This page can also help you understand this association by exploring:

- The link between attachment trauma and eating disorders

- How different types of insecure attachment affect eating habits

- How to access the right mental health support to recover from these conditions

What Are Eating Disorders?

Eating disorders are mental health conditions that disrupt a person’s relationship with food and body image. They manifest as extreme behaviours of food restriction or binge eating due to psychological distress rather than genuine physical hunger.

The most commonly recognised eating disorders include:2

- Anorexia nervosa: An intense fear of gaining weight and a distorted body image, leading to self-imposed starvation

- Bulimia nervosa: Cycles of binge eating followed by purging behaviours to prevent weight gain

- Binge-eating disorder: Recurrent bouts of eating large quantities of food in a short period due to a lack of control

- Other specified feeding or eating disorders: Disordered patterns of eating or restricting food that do not fit neatly into the above categories

Eating disorders affect people across all ages, genders, races, and socioeconomic backgrounds. The onset usually occurs during adolescence, a critical period of identity formation and social pressure. However, they can develop at any age.

What Is Attachment Trauma?

Attachment trauma occurs when early relationships with caregivers are disrupted by neglect, abuse, or inconsistent caregiving. It falls under relational trauma. This means attachment trauma occurs within the context of a significant relationship. It is also closely associated with complex trauma, which often results from repeated adverse experiences.

According to John Bowlby’s attachment theory, early bonds with caregivers form the foundation for future emotional and social development.3 When these bonds are compromised, children can develop insecure attachment styles that may persist into adulthood, affecting relationships and beliefs about the world. There are three types or “styles” of attachment, one secure and three insecure: anxious, avoidant, and disorganized (fearful-avoidant in adulthood).

Chronic stress resulting from early relational trauma also alters brain development areas associated with emotional regulation and memory.

How Are Eating Disorders and Attachment Trauma Related?

The relationship between eating disorders and attachment trauma runs both ways. Attachment trauma increases vulnerability to disordered eating by often leaving people with low self-worth. At the same time, the lived experience of an eating disorder, including secrecy and shame, can reinforce attachment insecurity.

The following sections take a close look at how different types of insecure attachment are related to eating disorders.

Eating Disorders and Anxious-Preoccupied Attachment

People with an anxious-preoccupied attachment style often experience an intense need for validation from others. As a result, they may develop eating disorders as maladaptive coping mechanisms.

Research indicates that people with anxious-preoccupied attachment are more likely to report dissatisfaction with their bodies.4 This reflects their internalized belief that their worth is contingent upon external validation.

Eventually, someone with this style might start seeing their appearance and weight control as a means of securing affection. Therefore, disordered eating behaviors are used as a way to control or alter the body to meet societal standards and to elicit positive reinforcement from others.

While unhealthy eating habits may provide temporary relief from emotional distress, they perpetuate a cycle of emotional instability.

Eating Disorders and Dismissive Avoidant Attachment

Dismissive-avoidant is a type of attachment where a child learns to suppress their emotions and rely on themselves rather than seeking support from others. Therefore, people with this type of insecure attachment may use food and body control as a way to manage emotions they cannot express.

For instance, studies have shown that avoidant attachment is linked to higher rates of restrictive eating and less help-seeking behavior.5 This may be because avoidant people strive for perfection using discipline as armor. Further, during times of stress, their perfectionism around body image could intensify.

In fact, a study on bariatric surgery patients found that those with avoidant attachment were significantly more likely to struggle with binge eating two years after surgery.6

Eating Disorders and Disorganized Attachment

Disorganized attachment typically stems from early caregiving that is both unpredictable and frightening.

A large-scale study found a significant link between disorganized attachment and uncontrolled eating, which in turn correlated with higher body mass index.7 The study suggested that disorganized attachment may drive impulsive, unrestrained eating as a default response, rather than eating as a calculated emotional regulation strategy.

This may come down to how people with disorganized attachment often struggle with managing overwhelming impulsivity and anxiety. Unlike those with avoidant attachment, many of them do not fall into restrictive eating styles. Instead, they are more likely to report binge-purge cycles, such as those associated with bulimia.

Reasons Why Attachment Trauma May Lead to Eating Disorders

Both attachment trauma and eating disorders are psychological at their core. Therefore, the fact that people with attachment trauma are significantly more likely to develop eating disorders is not a simple coincidence.

Several reasons explain why attachment trauma so often leads to disordered eating, including the following.

Using Food to Cope With Emotional Pain

Many children who do not receive secure parenting grow up without reliable strategies to manage their emotions. Their nervous system becomes sensitized to distress, but it also lacks healthy outlets for soothing.

When there’s a gap between emotional sensitivity and effective self-soothing, food can become a substitute for the comfort and security that were missing in early life.

This is because food interacts with the body’s reward systems. For example, research shows that highly palatable foods activate the brain’s dopaminergic pathways.8 Therefore, they can temporarily reduce feelings of anxiety and sadness.

In other words, the act of eating itself, even when disconnected from hunger, serves as a form of self-soothing, much like a child clinging to a caregiver would have done. As such, using food to cope with emotional pain can provide short-term relief. But over time, it deepens feelings of shame and self-blame when eating becomes tied to body image concerns.

Linking Self-Worth to Body Image

Attachment trauma can disrupt the foundations of self-esteem. Insecure attachment styles are strongly linked with low self-worth and increased sensitivity to rejection. Naturally, body image in such circumstances can seem like a way to win approval from others.

For example, a child who never felt consistently loved may grow into an adult who believes, If I’m attractive enough, I will finally deserve love. Such beliefs can appear as a survival adaptation to relational wounds.

Further, research finds that adverse childhood experiences and insecure attachment increase vulnerability to both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.9 Body dissatisfaction acts as a central pathway.

The sad part is that no number on a scale or compliment from others can replace the missing sense of unconditional worth that should have been nurtured in early relationships.

Being Unaware of the Present Moment

According to a study, childhood trauma is strongly associated with dissociative symptoms.10 These dissociative tendencies are frequently observed in people with eating disorders.

People who have been through attachment trauma often dissociate from the present moment. Since the body holds the memory of distress, awareness of the present can become overwhelming to these people. Therefore, to cope, many learn to numb out and escape into distraction.

Binge eating, for instance, creates a temporary dissociation; a sense of zoning out that allows escape from painful emotions. Restrictive eating, on the other hand, can dull hunger cues and bodily sensations so effectively that it blunts emotional awareness too.

Additionally, a lack of present-moment awareness may create a self-reinforcing loop. Because their emotions are overwhelming, someone may escape into unhealthy food-related behaviors. And because they rely on food to escape, they become even less practiced at sitting with feelings and listening to their bodily signals.

The Polyvagal Theory

The polyvagal theory was developed by neuroscientist Dr. Stephen Porges. It looks at how the vagus nerve, one of the longest nerves in the body, regulates our sense of safety and stress responses.11

The vagus nerve functions through three main pathways:

- Ventral vagal system: This system makes you feel calm and able to connect with others

- Sympathetic activation: Increases your heart rate, boosts the levels of stress hormones, and suppresses appetite.

- Dorsal vagal shutdown: This occurs when your body tries to freeze in response to overwhelming circumstances

A child with emotional trauma usually has a blunted ventral vagal (safe and connected) system. Instead, their baseline typically tilts toward chronic fight-or-flight or shutdowns.

People with eating disorders also show increased stress hormone levels and high heart rates.12 Therefore, disordered eating may be used to temporarily try to fix the body’s response back to the calm and safe system.

Coping Strategies for Eating Disorders Linked With Attachment Trauma

Disordered eating is not a weakness you should blame yourself for. It is, in a way, your body and mind trying to manage unbearable feelings with the limited tools they have. That said, it traps you in cycles of shame, isolation, and self-harm.

Therefore, healing should begin with learning about the triggers that gave rise to the eating disorder in the first place.

Some healthy coping strategies include:

- Reconnecting with the body in safe ways: Attachment trauma weakens your interoceptive awareness, the ability to sense hunger, fullness, or emotional states.13 Gentle practices like breathwork, stretching, yoga, or mindful walking can rebuild your trust in the body without judgment.

- Practicing emotional expression: Journaling, voice recording thoughts, or creating art are simple practices that can externalize emotion and reduce the buildup of unspoken pain.

- Building consistent, self-soothing routines: Sensory-based regulation strategies like listening to calming music, using weighted blankets, or holding something warm are known to downregulate stress responses in the body.

- Reach out to your loved ones for support: Social support is a proven protective factor against many mental health issues. It can reduce the eating disorder relapse risk and improve emotional regulation.

Mental Health Support for Eating and Attachment Issues

Healing from eating disorders rooted in attachment trauma almost always requires professional support. Therapy works on the deep emotional wounds that fuel unhealthy eating behaviors. Many different kinds of therapy have been reported to have worked for both attachment issues and eating disorders. They include:

- Attachment-based therapy (ABT): This form of therapy helps to create a safe, consistent relationship with a therapist who helps you re-learn what it means to trust and be cared for.

- Trauma-focused therapies: These include eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and somatic experiencing. They help you gently process traumatic memories and release the tension they’ve left behind.

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT): DBT is used to teach you practical skills to handle your emotions without feeling like you have to turn to food for control.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy-enhanced (CBT-E): One of the most researched treatments for eating disorders.14 CBT-E restructures your thoughts about food, weight, and body image.

- Group and family therapy: This form of therapy can provide you with corrective experiences to heal your relationship with caregivers as you both practice vulnerability in supportive environments.

If, however, you need emergency support, the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) offers a helpline and online chat for immediate action.15 The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) also provides a treatment locator for specialized eating disorder and trauma services across the U.S.16

Seek Professional Help at Mission Connection

Healing from eating disorders and attachment trauma is not something anyone should face alone. At Mission Connection, our licensed mental health professionals are available to walk with you through attachment recovery.

We offer different kinds of support, including outpatient care, a more structured partial hospitalization program (PHP), and inpatient treatment. We also have online therapy options that bring care to the comfort of your home.

Our team offers evidence-based therapies tailored to your unique needs, and if needed, we can integrate medication management as part of your recovery. Call us today to learn more about how we can help you heal attachment wounds or get started online.

References

- ANAD. (2023, November 29). Eating disorder statistics. National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. https://anad.org/eating-disorder-statistic/

- Balasundaram, P., & Santhanam, P. (2022). Eating disorders. PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33620794/

- Cassidy, J., Jones, J. D., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4pt2), 1415–1434. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579413000692

- Cheng, H. L., & Mallinckrodt, B. (2009). Parental bonds, anxious attachment, media internalization, and body image dissatisfaction: Exploring a mediation model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(3), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015067

- Gander, M., Sevecke, K., & Buchheim, A. (2015). Eating disorders in adolescence: Attachment issues from a developmental perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1136. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01136

- Leung, S. E., Wnuk, S., Jackson, T., Cassin, S. E., Hawa, R., & Sockalingam, S. (2019). Prospective study of attachment as a predictor of binge eating, emotional eating and weight loss two years after bariatric surgery. Nutrients, 11(7), 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071625

- Wilkinson, L. L., Rowe, A. C., & Millings, A. (2019). Disorganized attachment predicts body mass index via uncontrolled eating. International Journal of Obesity, 44(2), 438–446. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-019-0378-0

- Singh, M. (2014). Mood, food, and obesity. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 925. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00925

- Kovács-Tóth, B., Oláh, B., Kuritárné Szabó, I., & Túry, F. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences increase the risk for eating disorders among adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1063693. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1063693

- Boyer, S. M., Caplan, J. E., & Edwards, L. K. (2022). Trauma-related dissociation and the dissociative disorders: Neglected symptoms with severe public health consequences. Delaware Journal of Public Health, 8(2), 78–84. https://doi.org/10.32481/djph.2022.05.010

- Porges, S. (2009). The polyvagal theory: New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 76(Suppl_2), S86–S90. https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.76.s2.17

- Ávila, A., SanMiguel, N., & Serrano, M. A. (2025). Core symptoms of eating disorders and heart rate variability: A systematic review. Sci, 7(3), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7030089

- Brown, T. A., Vanzhula, I. A., Reilly, E. E., et al. (2020). Body mistrust bridges interoceptive awareness and eating disorder symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(5), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000516

- De Jong, M., Spinhoven, P., Korrelboom, K., et al. (2020). Effectiveness of enhanced cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(5), 717–727. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23239

- National Eating Disorders Association. (2023). National Eating Disorders Association. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2025). FindTreatment.gov. https://findtreatment.gov/